The story of Alma’s Cinderella

The music of Cinderella is a result of close cooperation between Alma and some imaginary composers from her invented country, Transylvanian. The libretto, however, is the result of close cooperation between Alma and very real people, over a long period of time. So a short history of how the opera evolved may be of interest.

Alma first heard the story of Cinderella when she was three years old. It seems to have had a special hold on her imagination from the very beginning, as she frequently requested for it to be read to her. It was also for some years a constant theme in her drawings.

One of Alma’s drawing of Cinderella and her step-sisters, from 2011.

Many of Alma’s favorite stories in the following years contained the central theme of the Cinderella story: a young girl who overcomes adversity after harsh or unfair treatment. One of her all-time favorite books was a fictionalized account of Nannerl, Mozart’s sister. In that children’s novel, Nannerl secretly writes a symphony, and is desperate for it to be performed. But she is ignored and dismissed by the adults around her, and sent to the kitchen instead. Nannerl doesn’t give up, however. She is determined to be recognized as a composer, and finally triumphs when her symphony is performed at Versailles. Unfortunately, this fictional account bears little relation to Nannerl Mozart’s real life. But the seven-year-old Alma was consumed by this story. She read the book over and over again, and for her the story was completely real. Her parents were loath to dispel the illusion.

Why did Alma develop such a strong identification with Cinderella-type heroines? Beyond the universal appeal of such characters, perhaps what drew her to them was her frustration at the discrepancy between her grand artistic ambitions and the reality of what she was able to achieve and how it was perceived by others. From the earliest years, she had a very strong urge to create art like a grown-up. When she finished reading a beautiful novel, for example, she immediately wanted to write one herself and have it published. When she was gripped by the operas of Rossini or Mozart, she saw no reason why she couldn’t write a full length opera too. But it was not always easy to convince grown-ups around her to take these ambitions seriously, and the resulting frustrations may be the source of the strong emotional identification she developed with the character of Cinderella.

When she was seven, Alma wrote a twelve-minute ‘mini-opera’ to a libretto by Elizabeth Adlington, which was loosely inspired by Neil Gaiman’s story The Sweeper of Dreams. Adlington’s story probably appealed to Alma because it was in essence another Cinderella story: a young girl applies to become a dream-sweeper, but is initially dismissed by three male executives because of the twin sins of being both young and “a female.” Through her talent and determination, she overcomes their prejudice and finally gets the job.

Alma’s short opera was staged in a music festival in Israel in 2013. It was sung, played and directed by first-rate professionals—a huge privilege for an eight year-old girl, and unbelievably exciting for Alma. Nevertheless, her burning ambition was to write a ‘real’ full-length opera, like a grown-up. And so, emboldened by her first success, she was now determined to start working on her new opera. And it was no great surprise what her chosen subject would be. It was also natural that Alma’s Cinderella would be a composer, and that the plot would turn around music.

Alma started collecting musical ideas for the opera in 2013, but she also enlisted melodies and musical motifs and inspiration from earlier years. At the same time, the plot of her future opera became one of the recurring subjects of family conversation at meal times. One element of the story that didn’t appeal to Alma was the slipper. Why should the Prince find Cinderella with a slipper, of all things? Why should the proof of her worthiness be the smallness of her feet?

I discovered the answer lay in the cultural history of the Cinderella tale, which goes back more than a thousand years. The earliest known version of the story is a Chinese fairy-tale from the ninth century about a girl named Yexian (or Yeh-hsien). The Chinese tale is remarkably similar to the story we know, and it ends with Yexian fleeing in haste from the festival and leaving one slipper behind. Yexian ends up marrying the King, when her foot fits perfectly into the tiny slipper. In China, a small foot was traditionally the mark not only of feminine beauty, but also of nobility. Indeed, for centuries Chinese women used to bind their feet from a young age in order to force them to be unnaturally small. So in the Chinese context, Yexian’s small feet made perfect sense as the proof of her true nobility. But once translated into a European context, the story was stuck with a random and irrational dénouement. (In the version of the Grimm brothers in particular, the ending turned into a grotesquely bloodthirsty scene in which the stepsisters hack off their own toes.)

But what should replace the slipper? Since the plot of Alma’s Cinderella had music at its center, it was natural that the Prince should find Cinderella through something related to music. But what exactly? The answer would eventually come courtesy of the famous Transylvanian composer Antonin Yellowsink, and it would be: a chord.

The first page from Alma’s biography of Antonin Yellowsink, which she started in January 2013.

In January 2013, aged seven, Alma started writing a biography of Antonin Yellowsink, one of the most illustrious composers in her imaginary land of Transylvanian. (Alma’s Transylvanian has nothing to do with the homonymous region of Romania. We have no idea where she heard this name and why she decided to use it as the name of her imaginary country.) Antonin’s biography was peppered with short musical excerpts from his oeuvre. A chapter that Alma wrote in October 2013 described Antonin’s first audience with the Empress, and the music that Antonin played to Her Majesty: “Ever more glorious the music became, growing in strength and power until it was like a mighty cathedral soaring lofty and pure in heavens.” Alma ends the chapter with an aside to the reader: “This beautiful expressive piece he wrote shall make you want to cry,” and this is followed by a short melody in F minor.

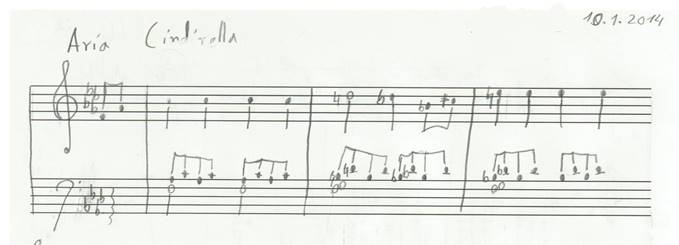

Alma herself liked Antonin’s sad melody so much that a few months later, in January 2014, she decided to ‘borrow’ it for her own opera and wrote a ballad for Cinderella to sing. It starts like this:

The first line of the ballad with Antonin’s chord, from Alma’s sketchbook.

The beginning of Antonin’s melody is unremarkable, a rising tonic chord. In fact it seems to be a quotation from the famous baroque aria, Tre giorni son che Nina, which Alma had played in her violin lessons when she was 5. After the first six notes, however, Antonin’s melody takes an unusual turn, with a chord that is rather unexpected and sounds very painful in the context: F-G-B-D (which partly resolves into F-G-B-flat-D-flat).

(Footnote: Alma herself described Antonin’s chord, in the language of figured bass that she thinks in, as a major 6/4/2 chord on F which then partly resolves into a minor 6/4/2 chord on F. In her revision of the opera in 2016, she introduced an even darker variant of this chord, which is used when the melody is heard for the second time. In this variant, the G in Antonin’s original ‘resolution’ is lowered to G-flat (in the middle of bar 2), in what Alma calls ‘beautiful parallel fifths with the melody’, and the phrase is deprived of even the partial sense of resolution that it had in Antonin’s original version.)

Alma’s darker variant of Antonin’s chord, from the revision of the opera in 2016.

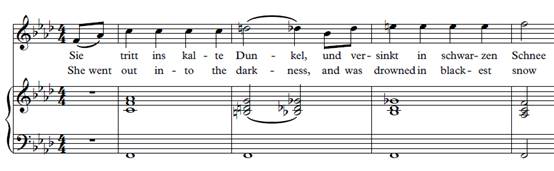

Antonin’s chord solved the problem of what would serve instead of the slipper in Alma’s story. Just before she flees, Cinderella sings to the Prince part of this sad ballad (“she went out into the darkness”), and the Prince is then haunted by the melody. He remembers the first conventional six notes, but cannot recall the next chord, with its hauntingly painful harmony on the word ‘darkness.’ The riddle of the melody finally provides the way he can find the mysterious girl who fled from the ball. The prince will sing the beginning of the phrase to every girl in the kingdom, and only the right girl will know how to continue it.

Another central pillar of the plot was added when we talked one day about Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, which my wife Janie and I had just been to see. We told Alma how Beckmesser goes off with Walther’s poem and sings it during the competition, with his own ridiculous music, which doesn’t fit the words. The idea appealed to Alma very much, and she wanted to integrate something similar in her own opera. But since Cinderella was a composer, she wanted a melody to be stolen, rather than a poem. Cinderella’s melody is then sung to foolish and unfitting words by the step-sisters, so in effect, it became a mirror-image of Die Meistersinger. Alma had just the melody for the ‘competition song’: an exuberant aria which she had dreamt up in a state of high excitement during a long car journey in December 2012, and which she ran to play at the piano the moment we got back home.

Two arias thus became the two central pillars of the musical plot of Cinderella: the sad ballad (“When the Day Falls into Darkness”) with Antonin’s painful chord, and the exuberant ‘competition song,’ composed by Cinderella and stolen by her step-mother. Of course, the Prince had to be the poet behind the words that Cinderella set to music.

In order to help turn these ideas into an effective dramatic structure, we enlisted the help of Elizabeth Adlington, who had written the libretto of The Sweeper of Dreams. She came up with some brilliant ideas for shaping the flow of the plot. For instance: how can Cinderella come across a poem written by the Prince, without knowing who wrote it? Adlington suggested that Fairy as the match-maker, and she devised a forest scene in which the Prince, in frustration, plans to throw away his book of poems; but he then runs into a poor old woman (the Fairy), and he gives her the book as kindling material, to help her light her fire. The Fairy later gives the book of poems to Cinderella, without telling her who the author is.

Meanwhile, Alma’s musical collaboration with Antonin Yellowsink continued apace. Antonin’s themes provided the inspiration for quite a few melodies in the opera. But sometimes the inspiration also went the other way. Alma reported one day that she had had a composition lesson with Antonin, and had played to him a jolly Waltz that she had composed for the Royal Ball. Antonin was apparently inspired by Alma’s theme, and developed it in a completely different direction. He turned it into a slow, mysterious and harmonically more adventurous passage, which Alma in turn borrowed from him in order to depict the dawn at the beginning of the overture. The Waltz theme thus turned into one of the recurrent motifs in the opera.

During 2014, Alma continued to gather musical ideas, at a very leisurely pace, for what she thought was a long-term project to be realized in the distant future. But in early 2015, an invitation came from the opera director Julia Pevzner, who had staged Alma’s mini-opera The Sweeper of Dreams, to perform Cinderella, in Hebrew, at a music festival in the Galilee, in the summer of 2015. Of course, Alma was excited about the prospect. But the opera was not nearly ready, and she only had a few months to go! So suddenly, from being on the back-burner, finishing Cinderella became a matter of urgency.

The Dramaturg Eitana Medan-Moshe helped greatly and wrote the first version of many of the spoken dialogues. The poet Tsur Ehrlich wrote Hebrew lyrics for many of the arias. Alma worked on the music at breakneck speed, and in true operatic tradition, she finished composing the Overture the day before the first orchestral rehearsal!

After the performance in Israel, Alma took a break from Cinderella. But in early 2016, a young Austrian opera ensemble, Oh!pera, invited Alma to stage Cinderella in Vienna, this time in German. And so in the spring of 2016, Alma started working on the opera again. The second half of Cinderella in particular was not yet fully developed, because it was put together so quickly for the performance in Israel. Alma added an enormous amount of new music in 2016, and also heavily edited some of the existing scenes. The original chamber version was scored for only six musicians, but in Vienna she had a small orchestra at her disposal, so she re-orchestrated the opera for an ensemble of twenty.

In 2017, Alma received an invitation from the Packard Humanities Institute, to have her opera staged in the California Theatre in San Jose. For the first time, she will be able in December 2017 to see and hear Cinderella as she had originally conceived it in her mind: on a big stage, with a full orchestra in the pit, with a choir and with dancers! So in 2017 Alma has been re-orchestrating the opera again, this time for a full orchestra of more than forty musicians. She has greatly expanded the ball scene, and has added more music for the choir to sing at the ball and at the final wedding ceremony.

The writing of the lyrics for the arias and the dialogues was particularly complex, because it evolved, at different times, in three different languages: Hebrew, German, and English. In addition to Alma and to myself, various people contributed to the writing: Tsur Ehrlich and Eitana-Medan Moshe in Hebrew, Theresita Colloredo and Norbert Hummelt in German. Even if their precise words cannot be heard in the English version of the text, their ideas inspired the English lyrics. Meredith Oakes helped greatly with the English translation. Janie Steen and David Packard contributed additional lyrics in English.

Guy Deutscher

September 2017